Influence on and by the work of Ilf and Petrov

Their predecessors

It has often been stated that Ilf and Petrov wrote in the satirical

tradition of Gogol and Saltykov-Shchedrin. This is true, of course, though it

does not do justice to Gogol, who was much more than a satiricist. (And so,

incidentally, were Ilf and Petrov, see elsewhere on this site.

However, I think few will object that they were satiricists, more so than Gogol.)

If you want to learn more about the issue of influences on the work of

Ilf and Petrov I advise you to read Shcheglov's magnificent

Спутник.

Two influences mentioned by Shcheglov which are less well-known than the

above-mentioned writers are Ehrenburg - in particular his

Julio

Jurenito - and the

Satirikon writers (especially Averchenko and Teffi), who

were unmentionable during Soviet times, because they emigrated after the

Revolution. Ilf and Petrov had certainly read their work and their influence

is beyond doubt.

Their successors

This is another subject for which I would very much appreciate

input by

readers.

Ilf and Petrov wrote in a literary tradition. Which later writers continued

this tradition?

I do not pretend to be an expert on world literature. Therefore I will discuss

some Dutch writers here and appeal to the reader

for input for other languages, including Russian.

Dutch

- Elsschot

- K. van het Reve

- Van Kooten en De Bie

English

- Nabokov

Dutch

Willem Elsschot (1882-1960) was one of the best Dutch writers of the 20th century.

Some would call him a Flemish writer, but his Dutch was impeccable and hardly,

if at all, recognizable as written by a Belgian. His first novel, Villa des Roses

(1913) is already a completely mature masterpiece.

Willem Elsschot (1882-1960) was one of the best Dutch writers of the 20th century.

Some would call him a Flemish writer, but his Dutch was impeccable and hardly,

if at all, recognizable as written by a Belgian. His first novel, Villa des Roses

(1913) is already a completely mature masterpiece.

One of the things which he shares with Ilf and Petrov is that his prose loses

much in translation. His style is sobre but very tense. It gives one the feeling

of great 'inflammability', to paraphrase Karel van het Reve (see below).

I mention him here because of his novels Lijmen (1924, translated in English

under the title of Soft Soap) and Het been

('The leg', 1938). The novels are told by Laarmans, a kind of alter ego of Elsschot himself.

The other hero is a man called Boorman, who is in various respects similar to

Ostap Bender. He is very intelligent and a bit aloof from society. He

understands human nature very well and uses this ability to make money.

Central in these two novels is a magazine with the comically pretentious

name Algemeen Wereldtijdschrift voor Financien, Handel, Nijverheid, Kunsten

en Wetenschappen, of

which Boorman is the director. He publishes very flattering articles about

companies and then sells large quantities of copies to this company, which

then is supposed to distribute it to its potential customers. The point is that

the companies in their optimism and vanity tend to order far too many copies.

Boorman's activities, like Bender's, are formally legal but border on crookery

and sometimes contain an element of blackmail.

The Laarmans character resembles Vorobyanninov in some respects. He is less

smart than Boorman and makes mistakes. Like Vorobyanninov he is sometimes ordered to keep

silent during meetings and also his name is changed like Vorobyanninov's.

Lijmen ends with a very succesful transaction with a small elevator

factory to which Boorman sells 100,000 copies of the magazine. The factory

is the property of a married couple - the wife, a rather pitiful

character with a sick leg, closes the transaction. When they realize that they

absolutely do not need 100,000 copies, it is of course too late. In

Het been remorse hits Boorman. The mega-transaction has not made him

happy, like Bender's million does not make him happy in The Little Golden Calf,

though for different reasons. Boorman now tries to buy back the copies, but

the wife, driven by a stubborn feeling of honour, does not let him. Only

at the very end he succeeds - the ending is happier than that of The Golden

Calf.

Elsschot was interested

in the Soviet-Union and like many other western intellectuals was optimistic

and moderately positive about the developments in the country.

As far as I know, however, he did not know Ilf and Petrov.

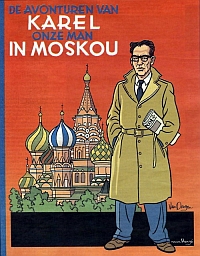

Drawing by Peter van Dongen

Drawing by Peter van Dongen

Karel van het Reve (1921-1999) is not primarily known as a novelist but as a publicist

writing about diverse subjects, including literature, religion, Darwinism,

Freud and many others. He is famous for his crystal-clear, elegant style, his

erudition, humour and wit.

Son of a active communist, in his young years he firmly believed in the

communist cause, but after the war he lost his 'faith' and became a very

outspoken anti-communist, which he remained for the rest of his life.

He studied Russian and wrote his PhD thesis on the esthetics of Soviet-Russian

marxism. In 1968 he was correspondent

in Moscow for the Dutch newspaper Het Parool. He wrote about dissidents

like Belinkov and Amalrik and supported them. Van het Reve was the person who

first brought Sakharov's

Reflections on Progress, Peaceful Coexistence, and Intellectual Freedom,

to the attention of the public.

In 1957 he was appointed Professor of Slavistics in Leiden. He wrote a very

interesting - if somewhat controversial - history of Russian literature up to

Chekhov. Van het Reve wrote a lot about Russian literature, but his interest was mostly

in the 19th century and in 20th century dissident writers.

There is however a rather curious mention of Ilf and Petrov in his Collected

Works (my translation):

"It is very interesting to observe how readers who like a book get attached to the

translation in which they happened to read it. When I was about sixteen years old,

I read The

Golden Calf by Ilf and Petrov in a Dutch translation by

S. van Praag. It was called Een millionair in Sowjet-Rusland. I got so much

attached to that text that I have never wished to read the Russian original. 'Gravin

loopt krankzinnig van angst in vijver' [Графиня изменившмся лицом бежит пруду - PJ]

is for me the original text [...]" (Van het Reve then proceeds to state that he

understands that this is an inadequate translation.). This truly baffles me. He was Professor in

Slavistics at the time but apparently did not think he simply had to read this

book in Russian. Whereas when writing about English or German literature he

always quoted in the orginal language.

Anyway, he definitely read and admired The Golden Calf. When

after his death

his library was auctioned to raise money for the publication of his Collected

Works, I bought his copy of Как создавался Робинзон.

Besides his essayistic work Van het Reve wrote two novels. The second, Nacht op de kale berg

('Night on the bare mountain', 1961), is the one I want to discuss here. The two

heroes, Joop Flavius and Bram van Heel, form another Bender/Vorobyanninov

pair, though they may rather be inspired by Elsschot's Boorman and Laarmans,

since Van het Reve admired Elsschot very much - this novel contains a few

hidden references to Lijmen.

The plot of the novel has some

striking similarities with The Golden Calf. The two heroes meet a very

nice girl, who is just as attractive and morally stable as Zosya Sinitskaya.

She is taking care of an elderly gentleman, whom 'she would not marry even for

a million guilders'. "Would you marry one of us for a million?" Flavius asks.

Well, she might consider it. They agree to meet again in exactly one year and

the two friends set out to gather a million. Flavius concludes that the best

way to earn a million on such a short term is 'to very urgently ask for it', so

that it will be 'handed on a golden platter'. He organizes a religious sect

(the novel is, among other things, an anti-religious satire), whose believers

are supposed to contribute 10 percent of their income to the building of a

Temple. (Dutch readers who consider reading the novel are advised to skip

the next part, since I will reveal the plot.) After some adventures the friends

really manage to gather a million. However, when they present the money to

the girl, she is flabbergasted and says: "You should not have done that.

I will not accept the money." After a short discussion she walks away.

And then they do what Ostap considered doing as well, but rejected as

'пижонство, гусарство': they burn the money. And then there is a

marvellous, brilliant final twist at the end, which I will not go into here.

To me the similarities are striking, even though Van het Reve was following

in the footsteps of Elsschot rather than Ilf and Petrov.

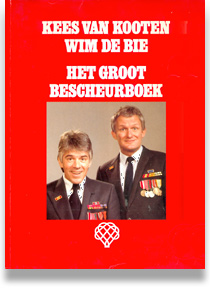

Finally I cannot help mentioning Van Kooten en De Bie here. They were

a famous television duo, who presented satirical sketches on television for more

than twenty years. Their satire was not unlike Ilf and Petrov's: sometimes

with ambiguous irony, leaving the reader in doubt what their real view was. And

most importantly, with a great feeling for language. Like Ilf and Petrov they made

a great contribution to their native language, creating words and phrases

which are still used, often without the user being aware of the origin.

Finally I cannot help mentioning Van Kooten en De Bie here. They were

a famous television duo, who presented satirical sketches on television for more

than twenty years. Their satire was not unlike Ilf and Petrov's: sometimes

with ambiguous irony, leaving the reader in doubt what their real view was. And

most importantly, with a great feeling for language. Like Ilf and Petrov they made

a great contribution to their native language, creating words and phrases

which are still used, often without the user being aware of the origin.

Like Ilf and Petrov they were immensely popular, not only with the cultural

elite but also with the 'general public'. And even young people, from after the

television days of Van Kooten en De Bie, generally know their name and have seen

some of their sketches.

They are both writers as well. Some of De Bie's short stories are

very close to Ilf and Petrov's short stories in their tone,

style and subject matter.

And they wrote together as well: between 1972 and 1986 they published a

so-called 'Bescheurkalender' (a pun on scheuren, 'tearing off', and

zich bescheuren, 'laughing out loud', i.e. a humorous block calender)

every year. In 1986 a magnificent anthology

of these calenders appeared: Het Groot Bescheurboek.

I have no information about their having read the work of Ilf and Petrov.

English

Sergey Gandlevsky suggests a relationship between

Vladimir Nabokov and Ilf and Petrov.

In an interesting

article in the magazine Citata he

first discusses general similarities between the works of Nabokov and those of

Ilf and Petrov and

then more in particular points to Lolita as being in a sense a more

modern, American version of the Bender novels, with Humbert Humbert of course

in the role of Bender, travelling the country and having to deal with its

petty bourgeois inhabitants, just like Bender.

Sergey Gandlevsky suggests a relationship between

Vladimir Nabokov and Ilf and Petrov.

In an interesting

article in the magazine Citata he

first discusses general similarities between the works of Nabokov and those of

Ilf and Petrov and

then more in particular points to Lolita as being in a sense a more

modern, American version of the Bender novels, with Humbert Humbert of course

in the role of Bender, travelling the country and having to deal with its

petty bourgeois inhabitants, just like Bender.

Personally, I think this is a bit far-fetched, although some similarities are

certainly present. However, if Nabokov really had Bender in mind when

creating Humbert Humbert, he would have built-in some obscure allusion or

hint, and such an allusion has not been identified as far a I know.

Nabokov

has alway rejected the idea of Lolita being a satirical novel about

America: "Satire is a lesson, parody is a game," he used to say. He disdained

filologists who approached Gogol only as a satiricist, and I am sure that,

would he have teached about Ilf and Petrov, he would not have treated the

satirical aspect of their novels very extensively. On the other hand, I think

one cannot deny that Lolita does have some satirical elements.

To sum up, I do not think that Nabokov consciously hinted at Bender in his

creation of Humbert Humbert, but I do think there is some relationship to be

seen, and comparing Lolita and the Bender novels is a potentially

useful exercise.

It is also interesting to compare the

travels

of Humbert Humbert and Nabokov in America

with Ilf and Petrov's American roadtrip.

We know that Nabokov admired Ilf and Petrov. See for more information the Citata

article mentioned above.

Document history of this page:

First online - 18/11/2010

Last minor changes - 12/01/2011

Last major changes -